Berlin, Europe, Democracy, Devolution.

A brief holiday stirs some thoughts on the wider context of devolution.

Berlin had glorious weather in early May, giving us the opportunity to do a lot of walking, not least between museums. The city was of course at the heart of the Cold War and the divide between Western and Eastern Europe after 1945. This trip set me thinking about Europe and the context of the making of devolution in the 1990s. Devolution to Wales and Scotland gathered strength in the aftermath of the democratic revolutions in Eastern Europe. I am not, of course, claiming cause and effect - local conditions in Wales and Scotland, and of course separately and distinctly, Northern Ireland, were far more important. But there was a wider context that is worth reflection.

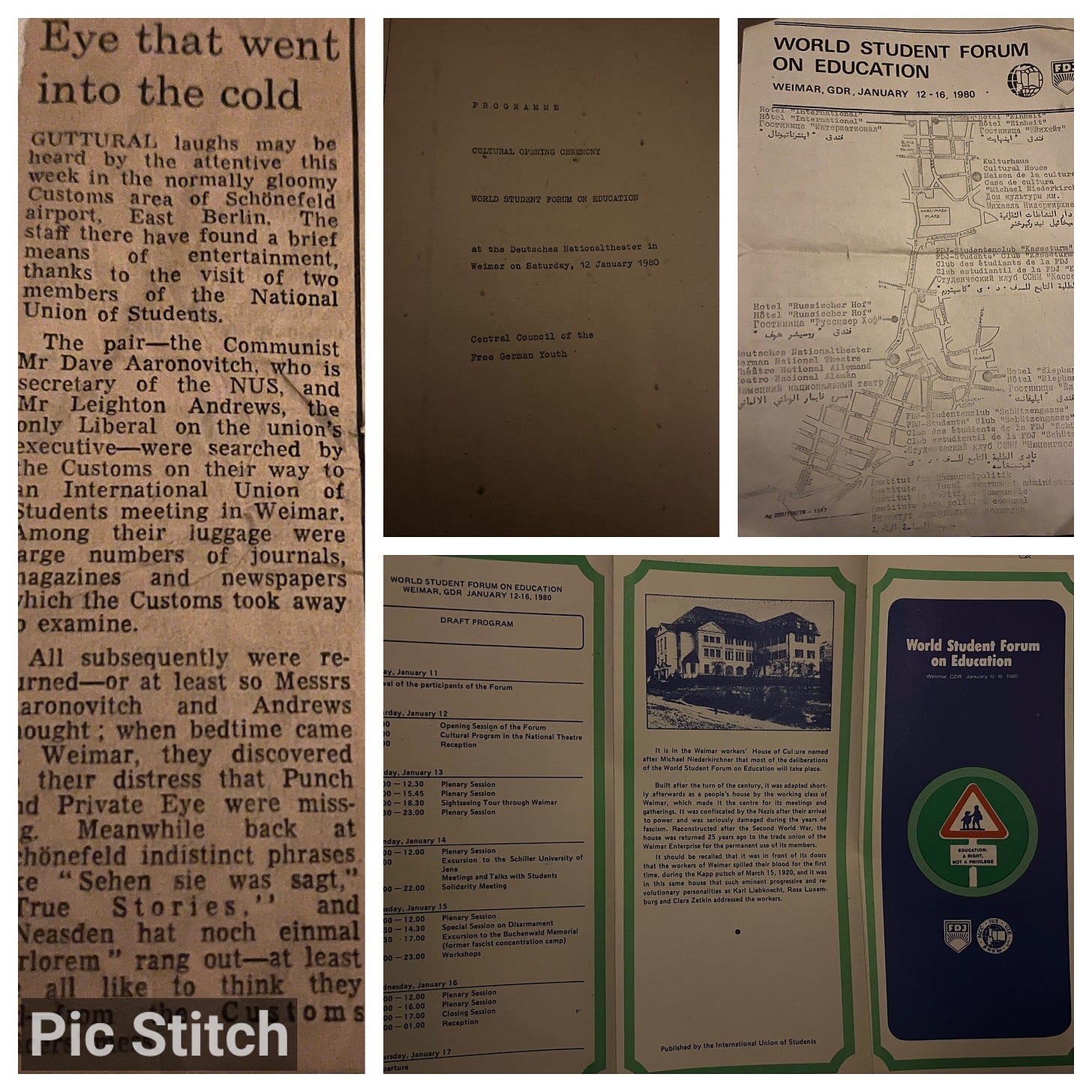

Berlin stirs memories. My first visit to Berlin was in January 1980. I was a delegate from the National Union of Students UK Executive to the World Student Forum in Education in Weimar, East Germany, along with other executive members David Aaronovitch and Mike Goodman. We were accompanied by NUS staff member Stuart Appleton. I think I had to get a passport especially for the trip. It might well have been my first visit overseas. We couldn’t afford foreign holidays when I was growing up and I never got into the habit of inter-railing as a student. That passport was later stolen in a burglary in the house I shared in London, so I can’t look up the details.

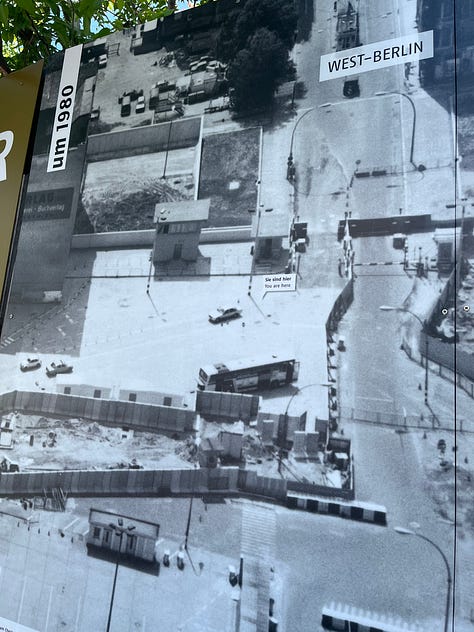

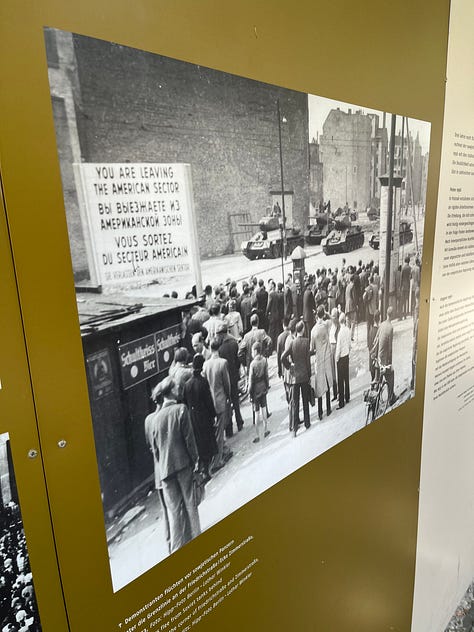

To get to Weimar, we first had to go to Berlin. We landed I think at the old Templehof airport, and arrived in West Berlin about 10.30 at night. We took a taxi to Checkpoint Charlie. At midnight it was surprisingly quiet, I noted in my diary at the time. Everything seemed a bit low key. The border guards conducted the entry process stiffly but politely. It was very cold - about minus 6, I think, and the snow was packed thickly on the ground. Rabbits hopped back and forward between East and West. We had to compete an Erklarung saying how much foreign money we were bringing into the country.

‘Are they capitalist rabbits or communist rabbits?’ I said to David.

“Do rabbits recognise class distinctions?’ he replied.

‘No’.

“Well then, they’re communist rabbits’, he replied.

Copies of Punch and Private Eye were confiscasted from us. ‘Verboten’, we were told. The guards ignored copies of the New Statesman attacking the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. An enterprising NUS press officer got this into the Guardian diary, although the details reported as to which border crossing it was are wrong (see below).

By now it was 12.30, and our hosts, the Free German Youth (FDJ - pronounced Eff Day Yot) were nowhere to be seen. Later, in Weimar, after a concert given in the delegates’ honour, we uncharitably decided the FDJ were ‘a bloody funny lot’.

At Checkpoint Charlie we asked the guards to direct us to a hotel. One suggested the Metropole, which I now know had only been opened three years before. It was a way of earning foreign currency for the DDR, and charged room rates in West German prices.

‘Is it good’, we asked?

‘Alles gut’, he replied.

It was quiet as we walked to the hotel. A few empty buses trundled home. Two or three youths walked past shouting and joking. A police car sped by.

The hotel was too expensive for NUS budgets at 90DM a night (about £20). We were able to borrow a phone and managed to reach the FDJ hosts still in their office. Soon we were transported to a Youth Hostel to stay the night, and each given a bag containing food, oranges, sausage and tinned mackerel. It was now 2 a.m. Breakfast the next day was sausage, bread, jam and coffee. We left the next day on a coach to Weimar, passing through Berlin streets adorned with posters about peace, freedom and solidarity with the Soviet Union. Weimar is even colder, but that’s a story for another day.

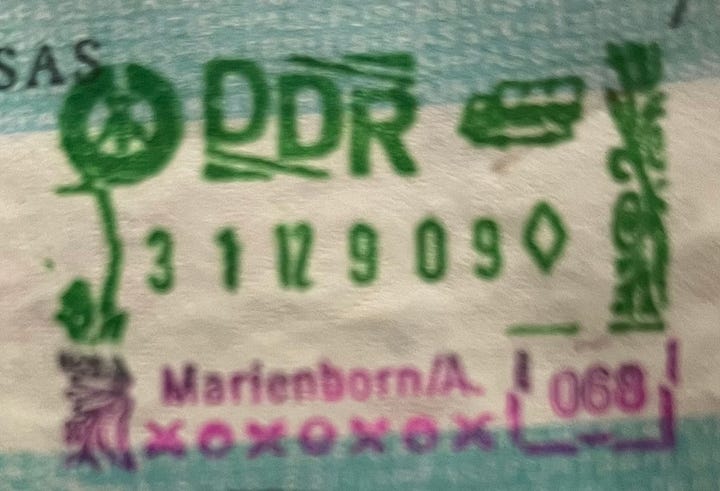

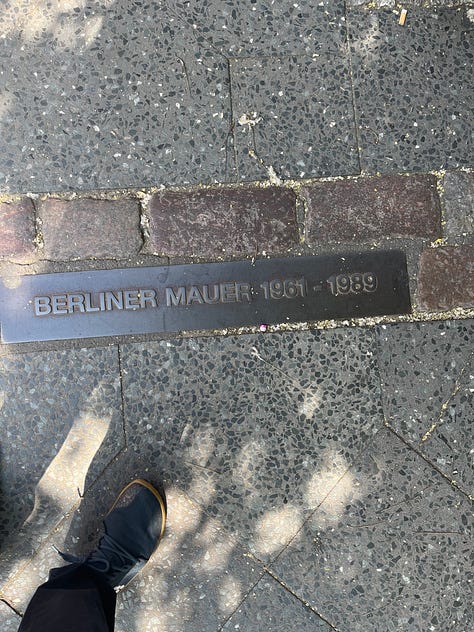

My next visit to Berlin was in December 1989. I had watched the news stories on 9 November 1989 about the wall being opened, and decided that Berlin would be the place to be on New Year’s Eve. So we drove there, entering the DDR via the Marienborn checkpoint, due East of Hannover (and exiting three days later via the Drewitz crossing).

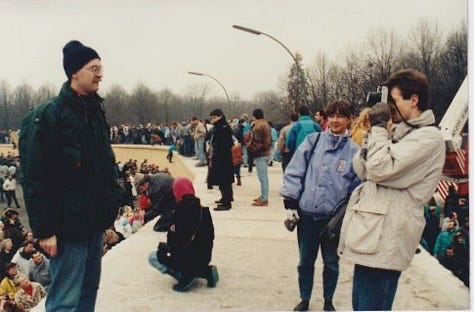

It was unquestionably the best New Year’s Eve party I have ever attended. In the afternoon of 31 December we walked up the Strasse des 17 Juni, and just past the Sovet War Memorial we could hear a slow rhythmic clinking.

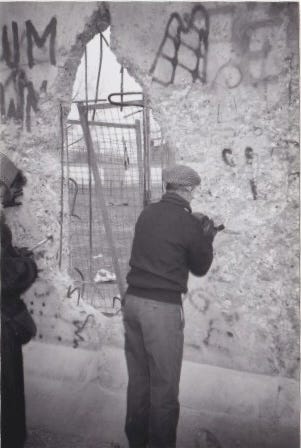

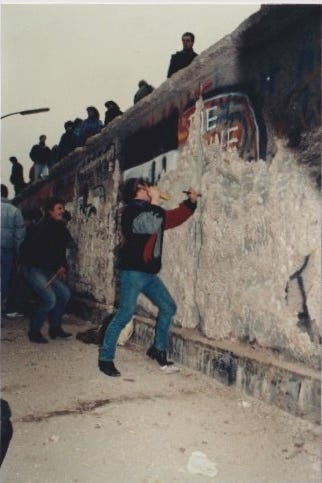

We soon found out it was people chipping away at the Wall with hammers and chisels to get souvenirs.

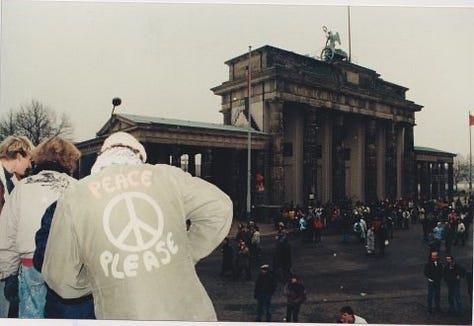

I joined people who were standing on the Wall, looking down to the Brandenburg Gate in the East.

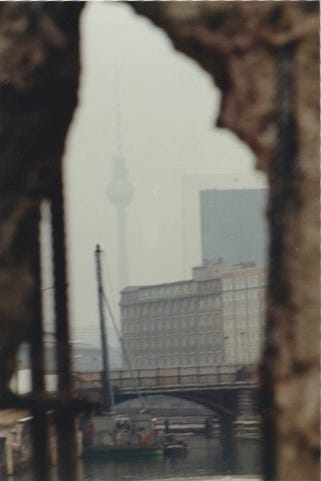

There were holes in the wall, just a few chinks at first, but in a couple of days you could take photographs through it.

We decided to cross into the East. We were turned away at the Brandenburg Gate, the guards saying ‘Nur Deutsche, bitte’ (only Germans, please). Foreigners had to cross elsewhere. But we were allowed to cross at the Brandenburg Gate in the evening, presenting our Zahlkarte to be stamped.

Soon the crowds were flowing to and fro between West and East with no interference whatsoever, with the VoPos (Volks Polizei) just looking on.

At midnight, there was an amazing explosion of fireworks on both sides of the Wall with people cheering and lots of noise. Some people got out sparklers.

East Germans shared some Sekt with us and spoke of their hopes for travelling abroad. The party was in full swing as people wandered back and forth across the wall and the border area. sat on the wall, surrounded sometimes by firework smoke.

Some climbed on top of the Brandenburg Gate and fired firework rockets from the ‘quadriga’ statue on top.

The East German flag on the quadriga statue was not popular.

Later it was taken down.

The Canadian flag made an appearance.

The West German flag, later the flag of unified Germany. was being waved in Unter Den Linden in the East.

We walked back unto the West later with no-one present to stamp our passports.

Berlin had a hell of a hangover the next morning, and the clear-up started on both sides of the border.

Of course, it wasn’t just Germany. Other countries in Eastern Europe liberated themselves.

Not all welcomed that. A crowd of East Germans supporting the liberation of their country turned up at the Dresden headquarters of the KGB on 5 December 1989, having over-run the local Stasi HQ. An officer there ringing for reinforcements found that ‘Moscow was silent’. His name was Vladimir Putin.

The next time I saw Berlin, in 1995, after unification, for a broadcasting conference when I worked at the BBC, it was just a fleeting visit, with no time to take photographs. The centre of Berlin, around Potsdamer Platz particularly, was a building site, the largest in Europe.

So nearly 30 years later, I visited again. It was a great trip. I’ll finish the travelogue before I link things back to democracy, devolution and Europe. We were fortunate with the weather, which was sunny every day and almost too warm for the clothes we had brought. Berlin, particularly walking from the Reichstag through the Brandenburg Gate to Museum Island and on to Alexanderplatz, has the feel of an old Imperial city. Grand boulevards, historic buildings from different eras, statues, views across the river.

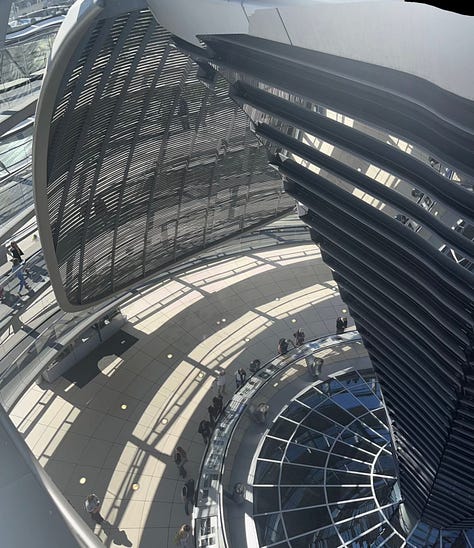

We visited the Reichstag, taking pictures across the City from the glass dome in the roof.

The Reichstag today looks different from how it looked in 1989, when very little of it was in use.

We visited the Holocaust Memorial, which is stunning, eerie, and majestic.

We saw the Caspar David Friedrich exhibition at the Alte Nationalgalerie.

We saw the Komische Oper’s production of The Marriage of Figaro, where the director, a Russian dissident, gave the Count a Putin-like fear of disease.

We visited Checkpoint Charlie - a revisit for me! - and the DDR Museum.

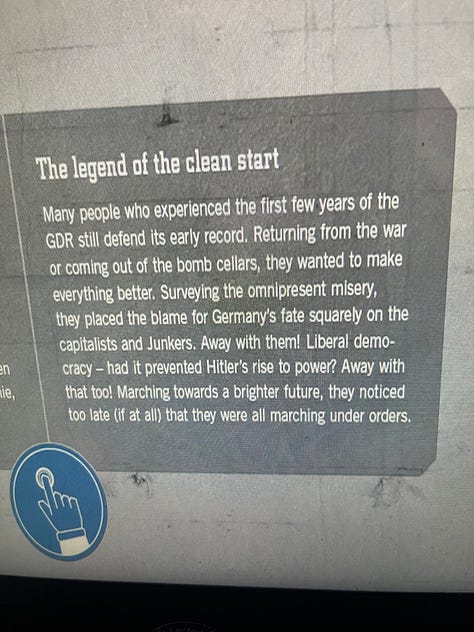

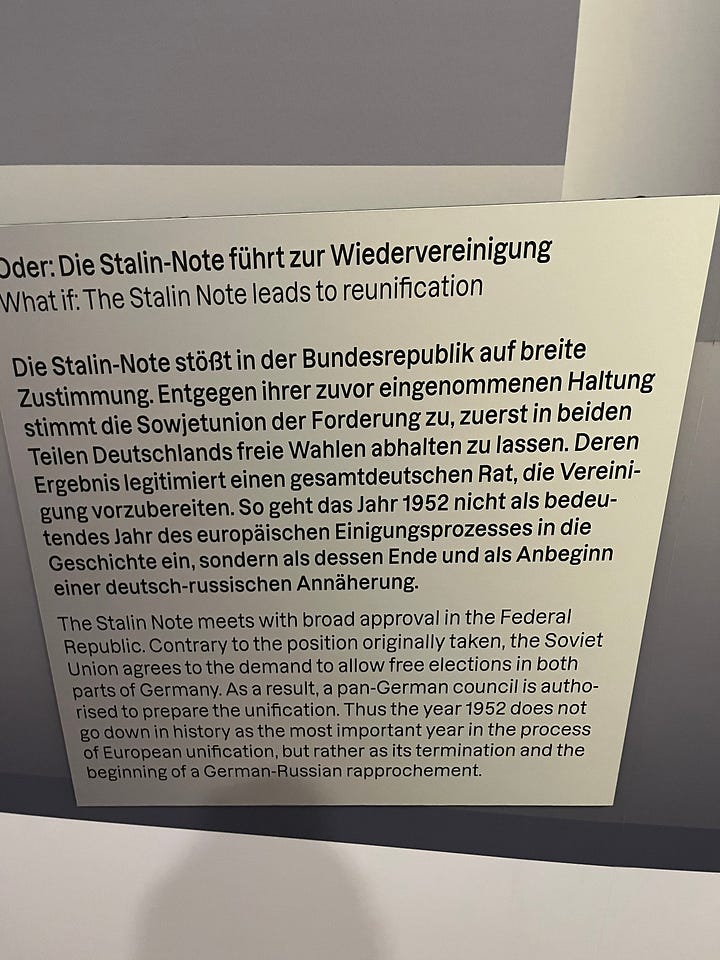

Meanwhile the German History Museum had a fascinating exhibition called Roads Not Taken, imagining how the course of German history over the last 150 years or so might have been different. Although ‘alternative history’ is something of an undergraduate way of considering the past, it threw a different lens on German history since the 19th century as we moved through the exhibition back from the present day. Here are two of the ‘What ifs?’ the exhibition poses.

Walking back along Unter den Linden after that visit, current history in the making enveloped us, with a demonstration against Russian interference in Georgia following the same route:

Having hosted a Ukrainian guest for nearly two years, we were pleased to see the signs of solidarity with Ukraine around the city.

Berlin of course was preparing for the European elections, which we in the UK will not be participating in for the first time since 1979.

So, Berlin, Europe, Democracy, Devolution.

I read Timothy Garton Ash’s article Big Germany, What Now? in Berlin the day after visiting the Roads Not Taken exhibition. In a thoughtful and sophisticated essay, he argues

The “End of History” was an American idea, but it was the Germans who lived the neo-Hegelian dream.

So history was going our way. Germany, Europe, and the West altogether had a model on which others would eventually converge. Globalization would facilitate democratization. True, Russia and China didn’t look terribly like liberal democracies, but as they modernized, they would get better. Western investment and trade would help them down history’s preordained track, while economic interdependence would underpin a Kantian perpetual peace.

Thus the country in which the Berlin Wall had come down enjoyed the greatest successes but also nourished the greatest illusions of Europe’s post-Wall era.

Devolution in Wales was of course born in this era. A time of hope. I know people had different reasons for voting Yes in 1997 - I’ve written about that here - but to vote for a National Assembly, whether you had been a die-hard devolutionist who had backed it in 1979, like me, or someone converted to it after Thatcher’s third election victory, as many were, was an expression of hope.

This period was, as many have argued subsequently, something of a ‘holiday from history’, an illusion shattered by the 9/11 terrorist attack, the Iraq War, and the Global Financial Crash.

By 2011, Wales had moved past the knife-edge devolution victory of 1997 to give a whole-hearted endorsement to a stronger Assembly in another referendum.

Devolution in Wales also took place in a European Union context, where it was possible to talk ambitiously of a Europe of the nations and regions, and where Wales was to benefit hugely from European structural fund investment. In 2016, of course, after years of austerity which hit Welsh public service and family incomes, Wales voted against European membership, marginally more emphatically than it had voted for devolution in 1997.

Then came Covid, which reminded us of international inter-connections. Then the war in Ukraine, which brought back images of division in Europe all over again. As Garton Ash writes:

The beginning of the largest war in Europe since 1945 reduced core assumptions of post-Wall Germany—political, economic, and military, but also moral—to rubble

Not only in Germany. Wales has responded generously to the war in Ukraine, but the challenges ahead are stark. Anyone wanting to help the Welsh effort should donate to the latest fundraising effort by Mick Antoniw MS. But the geo-political context in which devolution was born has gone.

That has practical implications too. Observing Scotland, the media scholar Professor Philip Schlesinger said in 2019:

The ‘constitutional question’ asks whether or not Scotland should stay in the United Kingdom and if so, on what terms. That matter is not closed. Here, it shapes our everyday life. In 2014, during the independence campaign, the Scottish public sphere was passionately Scotland–centred. In 2019, for the third year running, it’s overwhelmingly UK- centred. Because Brexit has crowded out Scottish matters in public debate. And this tells us much about the vagaries of a dualistic public sphere in a multi-national state….We’re politically and socially riven between those Scots who still want independence and those who still don’t. But we’re also Ukanians, to use Tom Nairn’s term, facing Brexit along with all the other Brits, and split again between those who want in, or want out, of the EU. For the past 20 years, devolution has supplied the institutional contours of Scotland’s public sphere. It was enacted when the UK was firmly inside the EU. The Brexit issue has overwhelmed the Scottish communicative space and marginalised the Scottish political voice in the UK. It has also raised many questions about the future of the present devolution settlement.

Welcome to Ukania.

Wales, unlike Scotland, has a more fragmented public sphere, rather than a dualistic one. Brexit certainly sucked the oxygen out of Welsh politics. Indeed, the legitimacy of the dominant devolution-supporting parties in Wales – Welsh Labour, Plaid Cymru and the Liberal Democrats, the progressive coalition which helped bring devolution into being - was severely tested by the Brexit referendum result which went against the stance they had been advocating.

Initially, I felt Covid had sucked the oxygen out of Welsh politics too. But as time moved on, paradoxically, whatever the enduring problems, the Covid pandemic gave people in Wales and across the UK a stronger sense of what devolved powers and devolution meant.

We recently marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the first Assembly election. Is the hope still there? Are we proud of what has been achieved overall? Writing about Scotland, the Scottish journalist Alex Massie said recently:

Difference and divergence were built-in from the offset; a feature not a bug.

Of course, he is right on that, but supporters of devolution have to want more than difference and divergence - delivery matters too. Here I am not going to go into the detail of the last twenty-five years. That is another project. For Scotland, Alex Massie writes:

The success of a parliament or a programme of devolution is harder to measure, however. To some extent it is not dependent upon outcomes at all. Politics is not simply a game of management. It is also a matter of feelings and sensibilities and geography and the vague but nonetheless real sense this is a distinct and coherent community. Devolution is one means of recognising that; whatever flows from it is for the future….

It has helped foster a Scotland that is in certain respects a more inward-looking, perhaps even parochial, place but also one that, despite a decade of sometimes bitter constitutional wrangling, more relaxed and secure in itself than might have been the case without devolution. In policy terms you may certainly argue that devolution has failed but politics is about more than mere policy.

Viewed like that, devolution is a means of recognising psychological realities as well as political ones. The survival of Scotland as Scotland has been one of the Union’s great triumphs for 300 years and devolution is part of that larger picture, that permanent accomplishment.

Holyrood has in some ways trumped Westminster as the primary focus of Scottish political attention. That is a kind of achievement too even if it is also one that comes at a cost. But here again we may observe an irony: Scots have no desire to see Holyrood’s powers reduced but they may appreciate a parliament’s importance without feeling compelled to love it….Has Scotland been governed well since 1999? Not especially. Would it have been governed better without devolution? Not necessarily. Does devolution recognise, indeed articulate, Scotland’s equivocation? Yes, in ways which may - or should - surprise its keenest admirers and critics alike.

Similar things could doubtless be written for Wales.

There will of course be some who will argue that Wales would have been governed better without devolution. Thankfully, the polls suggest that that is a minority pursuit. Over the last fourteen years, austerity, the loss of European funding, the savage cuts in welfare benefits, the failure to give Wales - through consequentials not awarded - its share of rail and other spending, have all taken their toll. Some decisions taken, and others not taken, in the early years of devolution when budgets were far more generous, had their own consequences.

We could of course ask the ‘What if?’ question that was posed in the German History Museum. What if Wales had voted no in 1997? No Assembly. £9000 university tuition fees from 2012. Academies and Free Schools in Wales. The Education Maintenanace Allowance completely abolished. No Future Generations Act. No free bus travel for pensioners or free prescriptions. And on and on and on.

Since 1999, at no point has any one political party had a majority in the Senedd. Policies have had to be negotiated. All political parties who have participated in the devolution project have their responsibility for where we are today. Success, stalemate, or disappointment, all share responsibility for the devolved Wales that we have.

And all parties face a real challenge in lifting turnout for Senedd elections to the level seen in UK general elections. That low turnout is a problem for legitimacy overall.

One of our best contemporary writers, Manon Steffan Ros, has written recently of the contrast between the hopes of her 14-year old self in 1997, and today’s general ennui about the state of politics in Wales and elsewhere.

In a personal and moving essay, based on her chapter in this book, she makes this important point:

The difference in the public perception of the Senedd versus the Houses of Parliament is stark here. An unpopular policy directed from Westminster will launch a tirade of complaints about the Tories or Labour, but no-one calls for the abolition of the Commons. But change the speed limit on some roads in Wales, and people will vehemently demand that the Senedd should cease to exist.

It’s a process, you know, devolution. A historical process. We all, as a great historian once said, have a role in the making of the Wales we want to see. Every generation has to win its democracy again and again, not take it for granted. And at the end of the day, the National Assembly, now the Senedd, is of course the only political institution the people of Wales have ever voted to create.

All Photographs ©Leighton Andrews and cannot be reproduced without permission.