Will there still be a Senedd in 25 years?

A provocation, not a prediction.

I am a little pessimistic about the future of devolution in Wales. For the reasons I list below, I think there must be an outside chance of a populist revolt against devolution which could result in the evisceration or abolition of the Senedd.

Hey, I hear you say, abolitionist parties have been hammered in the polls before. Meanwhile, regular polling demonstrates support for the endurance of devolution, I can hear my Cardiff University colleagues in the Wales Governance Centre responding.

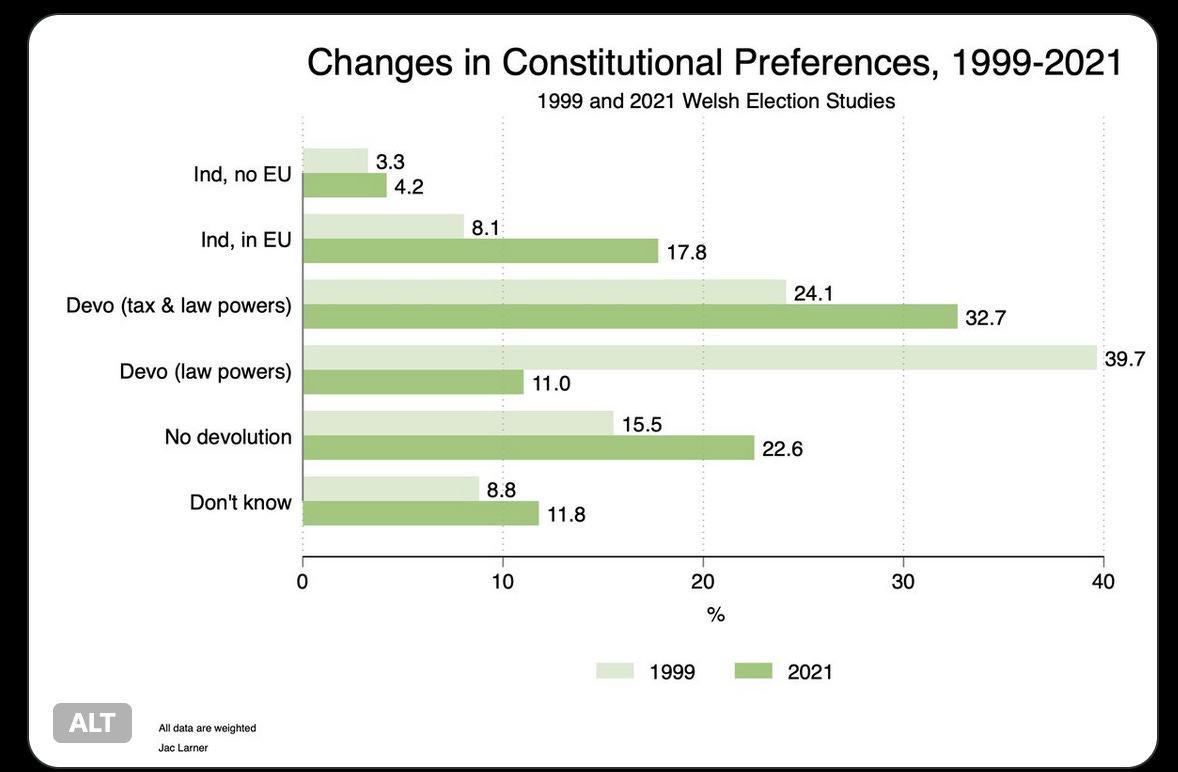

Yes, I know. Yes but no but, butt. Things are very different from either 1997, when the referendum scraped through, or 2011, when changes to the devolution settlement won an overwhelming majority.

I’ve been closely involved in both referendum campaigns. Even further back, I cast my first vote in the 1979 devolution when I was on the losing side.

I’m going to list the challenges, in the hope that we can re-kindle something of the spirit of 1997, or preferably 2011, in the next few years.

Here, in summary, are my concerns:

Populism, democratic backsliding, and the anti-institutional politics of the right and far right.

The legacy of austerity and continuing state failure.

A different geopolitical backdrop to 1997.

The ever-devouring demands of the NHS and social care.

The fragmentation of Welsh media.

The institutionalization of devolution’s strongest supporters.

The divide between standard-setters - the Welsh Government - and delivery partners (local authorities and others).

The danger of symbolic legislation rather than practical transformation.

The paradoxical tensions of a UK Labour government.

Populism, democratic backsliding, and the anti-institutional politics of the right and far right.

Let’s start with what I will crudely summarise as populism. Opinion polls have shown growing distrust in politicians. There is some evidence of a turn against democracy in general amongst some groups. There is a widespread sense that politicians are in it for themselves, that they are all the same, that they care more about the political system than about achieving real change. The Senedd will, in my view rightly, be a larger legislature after 2026, but no-one ever votes to have more politicians. Conditions are certainly ripe for a large bloc of right-wing populists in the next Senedd. Under threat from Reform, I see little likelihood that the Welsh Conservatives will spring back to a more pro-devo leadership any time soon. The populists cast themselves as the champions of the people against the elite. It’s an easy message in current conditions. And remember, fewer people turn out at Senedd Elections than UK General Elections, even in a low turnout year like 2024. In 2021, the figure was still only 46.8%.

The legacy of austerity and continuing state failure.

Then there’s the continuing legacy of austerity and state failure. There is evidence of a strong public sense, and certainly narrative, that the UK is broken and nothing works any more.

People’s experiences of state services are not wholly negative but there is real concern about the state of the NHS and more people are taking up private health options because of waiting lists. Wages and salaries have fallen in real terms since the Global Financial Crisis, with the UK the worst performer in the OECD.

Geopolitics.

Third, there is a very different geopolitical backdrop today than in 1997. Then, despite the Balkan wars, we were still celebrating the fall of the Soviet Union. The EU was an economic and political space that people wanted to join. The UK’s devolution programme was actively built in the context of UK membership of the EU, not least in Northern Ireland. Defence spending had fallen in real terms and was one of the reasons why domestic spending on public services could grow - the early years of devolution were years of rising budgets. There was also, in this context, intellectual space for a discussion of a variety of democratic options.

In 2019, Philip Schlesinger, one of the key chroniclers of communication, national identity and the public sphere, reflected on how, after Brexit, Scottish politics had been in a sense sidelined:

Brexit has crowded out Scottish matters in public debate. And this tells us much about the vagaries of a dualistic public sphere in a multi-national state…..

For the past 20 years, devolution has supplied the institutional contours of Scotland’s public sphere. It was enacted when the UK was firmly inside the EU. The Brexit issue has overwhelmed the Scottish communicative space and marginalised the Scottish political voice in the UK. It has also raised many questions about the future of the present devolution settlement.

Philip’s analysis of Scotland had much in common with the situation in Wales. Brexit crowded out devolution issues and the aftermath of Brexit was used by the Conservative Government to undermine elements of the devolution settlement and strengthen the UK voice, as well as bypassing the Welsh Government to seek to build direct relationships with local authorities. By contrast, the subsequent Covid crisis, as I wrote in 2021:

inserted the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish devolved voices into the UK political narrative and the UK media.

Covid briefly resurrected a devolution consciousness in Wales. Geopolitical tensions suggest, however, a likely focus on UK national defence and a continuing focus on the UK’s role in Europe and the world, against which the challenges of devolution will be seen as minor concerns.

The ever-devouring demands of the NHS and social care.

Covid, of course, has added to the pressures on the Welsh health service. Some time ago Mark Drakeford warned of the dangers of the devolved state in Wales becoming largely a National Health Service with a few other services attached but being squeezed as the health service absorbed more and more of the overall budget. At present, we continue to see growing waiting lists, and a crisis in social care that is crippling local authority budgets. It is highly unlikely that Wales can address these challenges on its own. Social care needs sorting, but there seems little evidence of that being tackled at a UK level.

The fragmentation of the Welsh media.

Back in 1999, it was possible to write of a devolution dividend enjoyed by the Welsh media, with extra investment into the newsrooms of BBC Wales, ITV Wales and the then Trinity Mirror group to cover the new institutions. Since the growth of social media and the dominance of digital advertising by Meta/Facebook and Google/Youtube the Welsh media has been eroded. Given the transnational nature of social media, this is serious. Some new ventures have been created, but older mainstream media are losing audience and punch. This includes what was a vibrant network of local weekly and indeed daily media.That is bad for demoracy and public discourse in itself, but it also means that the institutions whish had an interest in covering the Senedd are in decline.

The institutionalization of devolution’s strongest supporters.

In 1997, there were no devolved politicians. There were no politicians with experience of working in a devolved system. Inevitably, over the following years, individuals who had been at the forefront of the devolution campaigns became members of the new National Assembly (subsequently Senedd). The Welsh Conservatives adapted into the new institution, re-built their party, and by participating gave the new institution greater legitimacy. Today, one of the dangers I see is that the most enthusiastic devolutionists - devolution’s activists - have become institutionalised. I recall, back in 2010, when S4C faced serious cuts in its budget and funding mechanism, the generation of independent producers who had contained some of the most active campaigners for a Welsh language channel thirty years before seemed to have forgotten their campaigning spirit. S4C rolled over in the face of UK Government cuts, rather than seeking to appeal to popular opinjon in support of the channel and the language. Its activists had become institutionalised. I made this complaint privately to S4C executives at the time, and then said a bit more about it in my ministerial foreword to the 2012 Welsh Language Strategy:

This year will see the thirtieth anniversary of S4C’s first broadcast. That anniversary should remind us that the promotion and protection of the language has always depended on political support and grass-roots campaigning. The most damaging thing to happen to the Welsh language in the last two years was the decision by the UK Government to abandon the funding formula for S4C, set down in statute, without any effective public debate. The budgetary loss to the Welsh language in the five years to 2014–15 will be at least £60 million. The failure of the S4C Authority to maximise the cross-party public pressure that existed in Wales in defence of what was a statutory obligation on the UK Government demonstrated an institution whose pre-devolution mentality failed to understand the realities of post-devolution Wales.

For S4C in 2010, read the Senedd in 2024. Institutional participants become institutionalized, driven by the logics of their institution, turning away from the bigger picture. You see a concern about this starting to emerge in the podcast series recently launched by Lee Waters. Support for devolution can never be taken for granted and the day to day demands of managing the system cannot be allowed to elbow out the big picture politics. I know that Welsh Labour politicians, and politicians in Plaid Cmru and the Liberal Democrats, are out campaigning in their constituencies for their parties. But who, today, is making the principled case for devolution in the way that pro-devolution activists did in the 1980s and 1990s? I worry that some are too keen on talking down what we have:

The grass is always greener for some. Until they let the arsonists set it alight.

The divide between standard-setters - the Welsh Government - and delivery partners (local authorities and others).

There are in-built tensions in the Welsh devolved state between the Welsh Government as standard-setter and local authorities as key delivery agents with their own democratic mandate. This is a divide that precedes devolution and there have been various attempts to address it over time. I bear some of the scars on my own back and one day I will write an academic article (which no-one will read) about how not to do local government reform. Austerity has, however, made things worse, and it is a tribute to leaders on both sides that the system continues largely to deliver without real public tensions. The UK Conservative Government did seek, post-2016, through its City Deals and other funding initiatives, to drive a further wedge between Welsh Government and local government, but this was in general resisted. Continued austerity means that the system is under even more strain, and local people see local services closing or unable to meet demand. This is not, in my view, sustainable. Wales thankfully did do a council tax revaluation, unlike England, although the latest has been delayed until 2028. This is not something that can be continually put off, but there is little sign of revaluation happening in England, which could drive a future divide between Welsh Government and Welsh MPs.

The danger of symbolic legislation rather than practical transformation.

Legislatures are going to legislate. Execuitves are going to produce legislation for them to deliberate. Sometimes this is meaningful, sometimes it is symbolic. One of the challenges for the Welsh Government is capacity constraints. In the immediate aftermath of the 2011 referendum one constraint was - laugh not - an absence of sufficient numbers of government lawyers to support the legislative process. Delivery capacity is however the most common complaint of ministers and stakeholders. Allied to that is the difficulty all governments face in cutting back on what they are doing, taking a whole-of-government big picture view and recognising that certain programmes are no longer fit for purpose, when departmental logics may demand the maintenance of the programmes or the advancement of even more legislation. The Welsh Government is not along in this. Similar complaints have been made about Westminster, as I explain in my recent book. It would be a good time for our new First Minister to take a critical look across government on these matters and ask whether there is a whole-of-government approach to setting priorities.

The paradoxical tensions of a UK Labour government.

In the period 1999-2010, Labour Party solidarity provided a unified cultural framework with which to discipline relationships at Westminster and Cardiff Bay and maintaining good working relationships was key. The same is likely to be true now with Labour in power at both ends of the M4, and the noises in support of this are evident. But, as I have argued before, the transfer of power within Labour accomplished after the 2007 Special Conference and its endorsement of Rhodri Morgan’s agreement with Plaid Cymru, is now over. Labour has a structural commitment to Westminster elections as its dominant focus, and whatever Gordon Brown has in the past argued about competing sovereignties, Westminster parliamentary sovereignty is baked into Labour’s constitution. With the Senedd not attaining the same electoral legitimacy as Westminster in terms of turnout (although, paradoxically, the Senedd is the only political institution the people of Wales have actually voted to have), Westminster dominance within Labour seems inevitable while there is a UK Labour government with a landslide. This is likely to lead to tensions. The Assisted Dying debate could be the first example of this, since the Senedd, and key figures such as First Minister Eluned Morgan and Health Minister Jeremy Miles,are against it. The Assisted Dying debate brings into conflict devolved health responsbility and reserved criminal law responsibility.

Those of us with long memories also remember the tensions at play twenty years ago when Welsh Labour MPs were rightly concerned at the failure to bring down Welsh hospital waiting lists as fast as the UK Labour Government was doing. A contact group between Welsh Labour MPs and National Assembly Labour Members had been set up to work through tensions such as this. As a member elected to that group by the National Assembly Labour Group, I often got calls from Welsh Labour MPs concerned about this in the 2003-4 period. Meanwhile, on the other side of things, Alan Milburn’s GP contract deal seemed to many of us at the time to have undermined out of hours care in general practice in Wales. With UK Labour agian targeting hospital waiting times, but little evidence yet of any meaningful approach to social care, it is entirely possible that there will be renewed internal Labour tensions on these issues. Meanwhile, there are big issues which have an impact on Welsh funding where there may well be disagreements.

Underpinning all of my concerns is the question of delivery. Do people in Wales see the Welsh Government as delivering on their priorities or not? Do they see the added value of having an elected Senedd and a Welsh Government, or not? What will be the impact of a contest between Reform and the Welsh Conservatives for the right-wing populist vote? Valley communities proved open to the Brexit movement in 2016, and there were large numbers of Reform voters in 2024.

A decade ago, I would not have foreseen the UK leaving the EU. But we did, and Wales voted for it. In the 1980s, I remember that Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives abolished metropolitan counties in England and Scotland and the Greater London Council. Do not assume that the Senedd is here for ever. Take nothing for granted. We need a new cross-party movement cammpaigning for the principle of devolution. Will we get one? I’m not sure.

Interesting article, things are definitely changing, thank you Mr Andrews