I am a supporter of Keir Starmer’s Labour Government, so I tend to filter out 50% of the froth and noise that circulates around its activities. Though sometimes the difficulty is deciding which 50% to discount. Anyway, there’s no question that there has been a change in the mood music since I last wrote here in the middle of August, before setting off on holiday.

The Starmer Government started very brightly, especially for those of us who wanted to see competence and stability after the chaotic, sleaze-ridden years of the Tories. Cabinet appointments happened fast, and the first Cabinet meeting took place unusually on the Saturday after the election. There were striking ministerial appointments like James Timpson at prisons. Unworkable performative policies like the Rwanda scheme were dropped. Keir Starmer promised that the PM’s Independent Adviser on Ethics would be able to initiate his own investigations. The PM’s response to the riots was firm and uncompromising and won respect across politics. There was a clear commitment to making the government work in a coherent fashion, with Pat McFadden, who knows Number Ten from the inside and drove Labour’s election campaign, appointed as the PM’s Cabinet Office enforcer. More recently Sir Michael Barber has been brought back into government to help with delivery of the Five Missions (Michael has been called back by virtually every government since he left Downing Street’s Delivery Unit in the Blair years, perhaps a recognition of how difficult cross-government working can be, as I said in June).

It felt like a government that had, quietly, been preparing for office, ready to get on with the hard slog of governing from Day One.

At the end of September, things look a little different, and we have a spate of news items on tensions in the top adviser team, unwise acceptance of freebies, and the fall-out from the decision to means-test winter fuel payments.

Now, I officially started to receive my state pension last year, and I think it is ludicrous that I am entitled to receive the winter fuel payment. But at this stage, this isn’t the point. It feels like the government has lost control of the narrative.

All governments need what I call ‘narrative capacity’. In the UK, that ‘narrative capacity’ was enshrined as a core element of government practice by Alastair Campbell and the New Labour government in 1997, following the Mountfield Report on government communications, which, amongst other things, ensured that policy recommendations going up to ministers had to have some consideration of the communications impact of the policy.

It was entirely understandable that the Starmer government would rightly want to stick the blame on the Tories for the abject state of the public realm and infrastructure. As many have said since, that blame message also needs to be accompanied by a message of hope. Labour has reinforced the blame message at every stage - over prisons, the state of the grid infrastructure, the Grenfell cladding issue, the state of the NHS and so on. It’s also reinforced the economic blame message with its own decisions on winter fuel payments and the two-child cap.

The freebies issue is a separate problem, which, as Stephen Bush has said, has cut through to the public. Martin Kettle pointed out that there is not yet an updated ministerial code on the UK Government website. I checked, and he’s right. The Code is the one published by Rishi Sunak in December 2022.

Now, it doesn’t take long to update the Ministerial Code. Even if there is, to give the government the benefit of the doubt, a plan for a more wide-ranging reform of public standards, possibly giving stronger powers, for example, to the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments, it would have done no harm to have published an interim revised Ministerial Code, with a foreword from the Prime Minister on the commitment to high standards, and a reference to the new powers of the Independent Adviser. This would have taken no more than a few hours to redraft. And after the promises made in opposition, it should have been a priority.

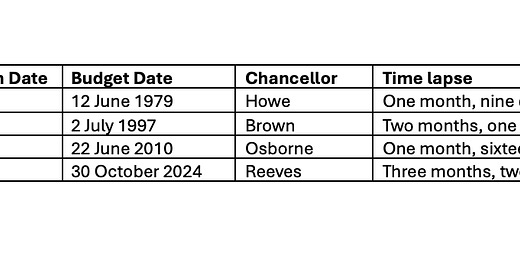

But the gaping hole in the Government’s narrative is the Economy, because that is driving everything else. There is a strong sense of ‘Waiting for Rachel’. The budget isn’t due until 30 October. This was a major strategic mistake. It’s the longest period between a ‘Change’ general election (when government changes between parties) and a Chancellor’s budget since at least the 1970s. Here’s a little table I just made:

Nor has this been augmented by an eye-catching announcement of the kind that Gordon Borwn made on the independence of the Bank of England in 1997. It is also worth bearing in mind that it was George Osborne’s Comprehensive Spending Review in October 2010, not his initial June Budget, which set out the Austerity programme in extensive detail. I know - I was a Welsh Government Minister at the time, and we immediately had to assess its implications for our next three years. It would have been open to Labour to have had a quicker budget this time, setting out the scale of the crisis, and thern a Comprehensive Spending Review later. I know that Rachel Reeves made a statement on the state of the public finances in July, and ministers have spoken endlessly about the £22 billion black hole. But that statement’s not the same as the production of hard numbers in a Budget.

The problem this narrative gap has left for Labour is that everything now depends on 30 October. There were effectively no significant new announcements at the Labour conference, an obvious place to launch new plans with some chance of heightened attention. That is not to say there was no meat in the speeches of the Chancellor, who promised no return to austerity, or the Prime Minister, who announced the public service ‘duty of candour’. But most policy announcements had already been made.

Additionally, potential big changes, such as changing the fiscal rules, have been telegraphed ahead with a lot more pitch-rolling than there was for the winter fuel allowance cut. The winter fuel allowance has now become the symbol of this government’s economic plans, rather than being seen as an outcome of a careful Budget process. The evidence that these winter fuel cut proposals had been put up to previous Chancellors suggests that the Treasury was happy to submit this to the current Chancellor fast as an example of the need for serious action to address the crisis left by the Conservatives. The winter fuel cut now exists however in isolation from the rest of the Budget package. It has determined the overall narrative. Meanwhile, a change in the fiscal rules would not now be unexpected. A failure to change them would be unexpected!

Keir Starmer’s first One Hundred Days expire, depending when you count from, on 13 October. Now, the ‘100 days’ concept is a bit of a totem. It comes to us from the American presidency: it was coined by Franklin D. Roosevelt in a radio ‘Fireside Chat’ as a description of the blitz of legislative and administrative action he took to combat the Great Depression. But the first 100 days is still a concept used to evaluate initial leadership performance in business and politics. The Institute for Government has published a guide written by a former Labour Secretary of State and a former Permanent Secretary on what to do – and what not to do – in the first 100 days of taking office. In a sense, it’s the supposed ‘honeymoon period’.

The Labour Conference happened within Keir Starmer’s first one hundred days. The Budget is happening outside them. Now that Budget really matters, if there is to be a chance to re-set the narrative and restore political grip.

Former Blair Political Secretary John McTernan recently published five principles for governing: use your power, bring back politics, extend your wings, rebuild your base — and govern in poetry. I’d add a sixth: pick the right enemies. After the Riots, Keir Starmer had the support of the public for picking the right enemies: the rioters, and Elon Musk. I’m not sure who decided to make it look like Labour wanted a fight with pensioners.

I had hoped to re-start this Substack earlier in September, but after we returned from holiday on 14 September it was straight into preparation for teaching. We began last week with the part-time MBA module on Global Challenges and Strategic Decision-Making, which I am co-teaching with fellow Profs Calvin Jones, an economist with strong, clear (and correct) views on climate change and regional inequality, and Maneesh Kumar, an expert on logistics and systems who has advised businesses and public bodies. I was looking at military and governmental decision-making. As I’ve said before, it’s no surprise that governments are so reliant on military planners for thinking about future threats and risks. Next week we start teaching that module to the full-time MBA students.

I will also start teaching my expanded ministerial module to our MA Politics and Public Policy students.

Our first topic next week? ‘Becoming a Minister - and the first 100 days’ !

Re the date of the Budget, your table is interesting, but does your criticism of deferring it to 30 October take account of any requirement of the OBR for a period of notice (is it ten weeks?) before a major fiscal event takes place, so that it can get its forecasting eggs in a row? Or am I completely wrong about that? If I’m right, the info in your table doesn’t provide a fair comparison, as there was no OBR to delay things in earlier times. (And having criticised the Truss/Kwarteng budget for not consulting the OBR beforehand, that was never an option for Ms Reeves this time!).