Make 2025 the year of nuanced tech regulation

And worry about Zuckerberg as much as Musk

The Financial Times’ word of the year in 2019 was ‘techlash’, the year when states and their regulators finally started to take on Big Tech social media and search firms more seriously. Then we got the pandemic, and Big Tech companies sought to re-align themselves as helpful to humanity. But the process of tech regulation didn’t go away, and from 2021, the Biden administration appointed people with serious anti-trust credentials to important roles in the White House, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Whether anti-trust action will remain at the heart of US policy on Big Tech under the new administration is anyone’s guess. Trump is transactional, and Big Tech bosses have been flocking to Mar-a-Lago to make friends, as well as making donations. Some, such as anti-trust activist Matt Stoller, are optimistic , noting that Trump launched the original anti-trust action against Facebook.

Whatever happens, the UK will be a minor player in tech regulation compared to the USA and the EU. But 2025 is the year when Ofcom should be acting on its responsibilities under the Online Safety Act.

Meanwhile, TikTok has gone dark in the USA - in other words, users in the USA are no longer able to use the app unless its ban is reversed.

TikTok has been described by tech antitrust scholar Tim Wu as one of China’s most useful strategic assets, ensuring Chinese spyware is embedded in 100 million phones in the USA.

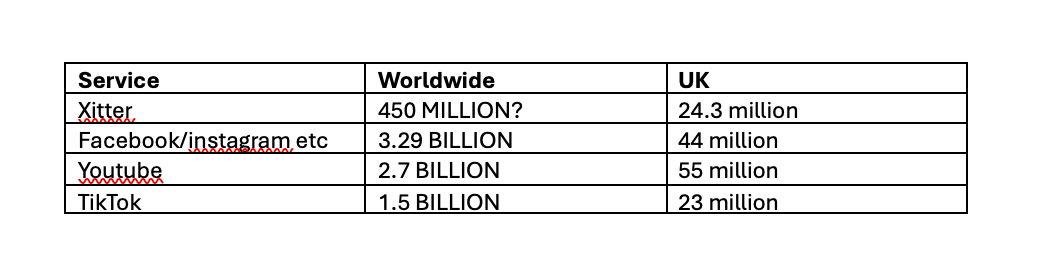

Sometimes political commentators get too fixated on Xitter. It’s worth reminding ourselves of usage of different social media sites worldwide and in the UK:

I have cobbled together these figures from a variety of sources. My objective is not absolute accuracy, but simply a reminder of the balance of use (with TikTok growing) between different services. People use these services for different things; there are different balances of use between age groups and between men and women; amount of time spent on each service daily and monthly is also important (and one way in which the services represent themselves to advertisers and the markets). I could have added in Snapchat (about 24 million UK users) and gaming services which allow user messaging as well, I guess, but this will do for now.

On the whole I worry more about Facebook and its family of applications more than I do Xitter. When I was an elected politician (up until 2016), I took the view that my constituents were largely using Facebook, while the political and media classes were using Twitter.

But all of these services are governed by proprietary algorithms. There are differences between them, and within Facebook between the Facebook and Instagram algorithms. However, the differences needn’t detain us for now.

Let’s turn to the statement by and subsequent interview with Mark Zuckerberg on 7 January and after. Emily Bell and Dave Karpf and Chris Stokel-Walker are well worth reading on this, and there’s a very good piece by Matt Stoller in his BIG newsletter here, but you have to be a subscriber to read it, so I will do my own summary of the Facebook developments.

Essentially, Zuckerberg has announced

Third-party fact-checkers would be scrapped

Crowd-sourcing community notes would determine what content is acceptable (Stokel-Walker rightly calls this ‘mob rule’)

Content moderation will move from liberal Califormia to Republican Texas

The algorithm will give users more political content based on their interactions

A Trump ally would be joining his board (Dana Whyte, CEO of the Ultimate Fighting Championship)

The successor to Nick Clegg in terms of global policy would be long-time Republican Joel Kaplan

He urged Trump to go after states around the world that seek to impose content moderation on Facebook.

Diversity, Equality and Inclusion programmes are ending in Meta

The changes to content moderation were endorsed by the Board of Facebook appeasers, originally appointed by Nick Clegg, known as the Facebook Oversight Board:

Meanwhile, the Financial Times reported that top Facebook advertisers were largely exempt from content moderation in any case. This should come as no surprise. After all, a Channel Four documentary on Facebook moderation procedures in 2018 showed a manager in the moderation team saying that the Page of the far-right UK leader Stephen Yaxley-Lennon (aka Tommy Robinson), which had been found to have violated Facebook’s community guidelines, would have to be referred up because of the number of followers he had.

It’s not new for US governments to challenge overseas states who seek to impose limits on Big Tech. International trade agreements, such as that between the USA, Mexico and Canada, had restrictions on such limits built into them. Even President Obama complained about the EU going after US tech companies. As Lina Khan told Rana Foroohar of the Financial Times in 2019:

“During the Obama years, there was a sense that, oh, Europe’s just going after these companies because they [Europeans] are protectionist. And I think that’s insulting. People are now recognising that, yes, there are issues.”

Khan has been able to regulate on those issues at the FTC since 2021.

In 2019, Zuckerberg, after Facebook had received serious fines from the FTC and the Securities and Exchange Commission, began to become concerned about TikTok. He called TikTok out for censorship in a speech at Georgetown university in late 2019. In remarks that chime with his recent statement, he set out his case on restrictions on speech and content. The positioning of Facebook against TikTok was a deliberate move for the Trump years, resonating with Trump’s approach to China. It was a useful pivot, and Zuckerberg pivots transactionally, depending on the political climate.

What will the new policy mean in practice? In March 2019, Facebook banned white nationalist groups and propaganda from its site. Facebook’s policy director for counter-terrorism, Brian Fishman, said:

We decided that the overlap between white nationalism, [white] separatism, and white supremacy is so extensive we really can’t make a meaningful distinction between them. And that’s because the language and the rhetoric that is used and the ideology that it represents overlaps to a degree that it is not a meaningful distinction.

At that time Facebook said that anyone searching on their site for white nationalist or white supremacist material would be redirected to the organisation Life after Hate, made up of reformed violent extremists who would be able to provide support and education. The decision, taken at Facebook’s Content Standards Forum, and apparently involving over 3 dozen executives across the company, came two weeks after a white nationalist terrorist attacked two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing 50 worshippers. He had announced the attack on the 8chan message-board and live-streamed it on Facebook. Facebook acted to try to stop viewing of the video.

Despite this, white nationalist sites continued to make use of Facebook. It seems likely that any blocking of them will now be dropped, just as Elon Musk has allowed white supremacists and racists access on Xitter. As Hope Not Hate has documented, social media has allowed the flourishing and distribution of far right ideas into the wider public and the political mainstream, and there is now a ‘post-organisational’ networking of far-right white supremacist propaganda. Facebook will be one of several social media sites which amplify this, but given the size of its user base, it will be one of the most powerful. Axios has a summary of the policy changes and what kind of offensive content will now be allowed on Facebook.

For nearly a decade, Facebook has had a problem with the political right over its moderation policies. In 2016, a particular crisis emerged for Facebook when Gizmodo reported former Facebook employees had suppressed trending news from conservative American sites. Zuckerberg allegedly had to re-assure conservative publishers that there would be no bias against them, and at the time human monitoring was reduced. Reform leader Nigel Farage had made similar complaints over the years.

The twists and turns of Facebook content moderation policies after 2016, when it feared a liberal backlash, and in response to terrorist incidents, is too lengthy to summarise here.

The likelihood is that these new policies will apply in the USA, and that Facebook will still have to abide by laws in other jurisdictions such as the EU and UK, but Facebook will urge Trump to impose penal tariffs or other measures on countries which seeek to regulate Facebook and its brands in ways that Zuckerberg doesn’t like. It’s not clear that the EU yet has a plan to deal with the impact on its rules-based approach of what has been called the madman theory by long-time international relations specialist Daniel Drezner. It’s not so long ago that the EU’s rules were considered as setting the standards for social media regulation on issues such as personal data, even by Zuckerberg. Those times are gone and the EU faces populism within its own borders. Meanwhile, the UK’s Online Safety Act has yet to be tested, and some suggest it can be a blunt instrument for smaller sites.

Researcher Robyn Caplan suggested some years ago that there were basically three levels of content moderation in place or necessary for different kinds of sites or platforms:

Artisanal: These teams operate on a smaller scale. Content moderation is done manually in-house by employees with limited use of automated technologies.

Community-Reliant: These platforms–such as Wikimedia and Reddit–rely on a large volunteer base to enforce the content moderation policies set up by a small policy team employed by the larger organization.

Industrial: These companies are large-scale with global content moderation operations utilizing automated technologies; operationalizing their rules; and maintaining a separation between policy development and enforcement teams.

It’s to be hoped regulation will respect these different scales - but Big Tech bosses such as Musk and Zuckerberg now appear to be committed to a Community-Reliant model when Industrial-level is needed.

What we can certainly be sure about is that they will stick with whatever model monetizes best for them - and if a far right white supremacist generates lots of clicks and attention that earns them advertising revenue, hey, what the hell. Allied to this of course are the proprietorial algorithms, including recommendation algorithms, which on many platforms drive people down the rabbit-hole to more and more extreme content.

Despite the new US administration, a series of legal cases are proceeding through the courts in the US against Facebook, Google and others, some of which threaten break-up of the Big Tech giants. These are sometimes hard to track, unless you are following Digital Content Next’s Jason Kint’s feed on Xitter. Zuckerberg himself has been deposed in one lengthy court-case.

For Facebook the cases currently proceeding include:

The claim that Facebook used allegedly ‘pirated’ content to train its AI system, LLaMa (Zuckerberg has been deposed in this case).

Shareholders have sued Facebook executives for harming investors by allowing the company to breach its 2012 privacy agreement with the Federal Trade Commission in the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Shareholders allege that the company overpaid the Securities Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission in fines (over $5 billion) to avoid Zuckerberg having to testify before the two regulators. Former Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg has been sanctioned by a judge for deleting potentially incriminating emails in this case. Zuckerberg has to give evidence. Apparently former Facebook board members Peter Thiel and Marc Andreessen have already been deposed in this case.

A case going on since 2018 in Northern California that Facebook inflated its advertising metrics.

Meanwhile, Google has been fighting a Department of Justice case that it should be broken up and forced to sell its Chrome web browser.

These cases illustrate something that I have said for a considerable time - regulating Big Tech is a process, it’s not about a single Act of Parliament or Congress or the EU. Or, as the lawyer David Allen Green wrote this month in an excellent article in the Financial Times:

regulation is an ongoing phenomenon

The build-up to the ‘techlash’ in 2019 was in part driven by a realisation amongst advertisers that social media companies, including Google’s Youtube, were placing their advertising alongside hate-filled or violent content, and they were worried about ‘brand contamination’. Organisations pulling their advertising in the short-term included the UK Government, the BBC, HSBC, Lloyds, McDonalds, Aldi, L’Oreal. The Havas advertising agency pulled advertising on behalf of 240 clients. Vodafone announced that it was pulling advertising from ‘fake news’ sites by whitelisting sites where it was prepared to advertise. Two of the biggest advertisers also took action: Proctor and Gamble slashed $200 million from its digital advertising budget without seeing any negative impact on its bottom line; Unilever said it would move money from sites that could not prove that the ads were being seen by humans rather than robots.

Understanding digital advertising is key to addressing the challenges of social media, but sadly few politicians understand its importance. I always believed that one of the reasons the UK Digital, Culture, Media and Sport committee was so successful in this field in the 2017-19 period was because its Conservative chairman, Damian Collins, had a background in the advertising industry. His work uncovered some of the sweetheart deals that Facebook had engaged in early on in respect of access to customer data, while cutting off others’ access to it.

Digital Advertisers may yet force changes to the policies of Facebook and Xitter. They’ve certainly upset Musk in the past. Meanwhile regulatory action continues to be one of the key risk factors identified by Facebook’s parent Meta in its quarterly filings with the SEC:

government restrictions on access to Facebook or our other products, or other actions that impair our ability to sell or deliver advertising, in their countries;

•complex and evolving U.S. and foreign privacy, data use, data combination, data protection, content, competition, consumer protection, and other laws and regulations, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Digital Markets Act (DMA), Digital Services Act (DSA), and the UK Digital Markets, Competition and Consumer Act (DMCC);

•the impact of government investigations, enforcement actions, and settlements, including litigation and investigations by privacy, consumer protection, and competition authorities, among others;

•our ability to comply with regulatory and legislative privacy requirements, including our consent order with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Regulation is a social process, even against anti-social media, and it’s up to us and our elected representatives to keep the pressure on.